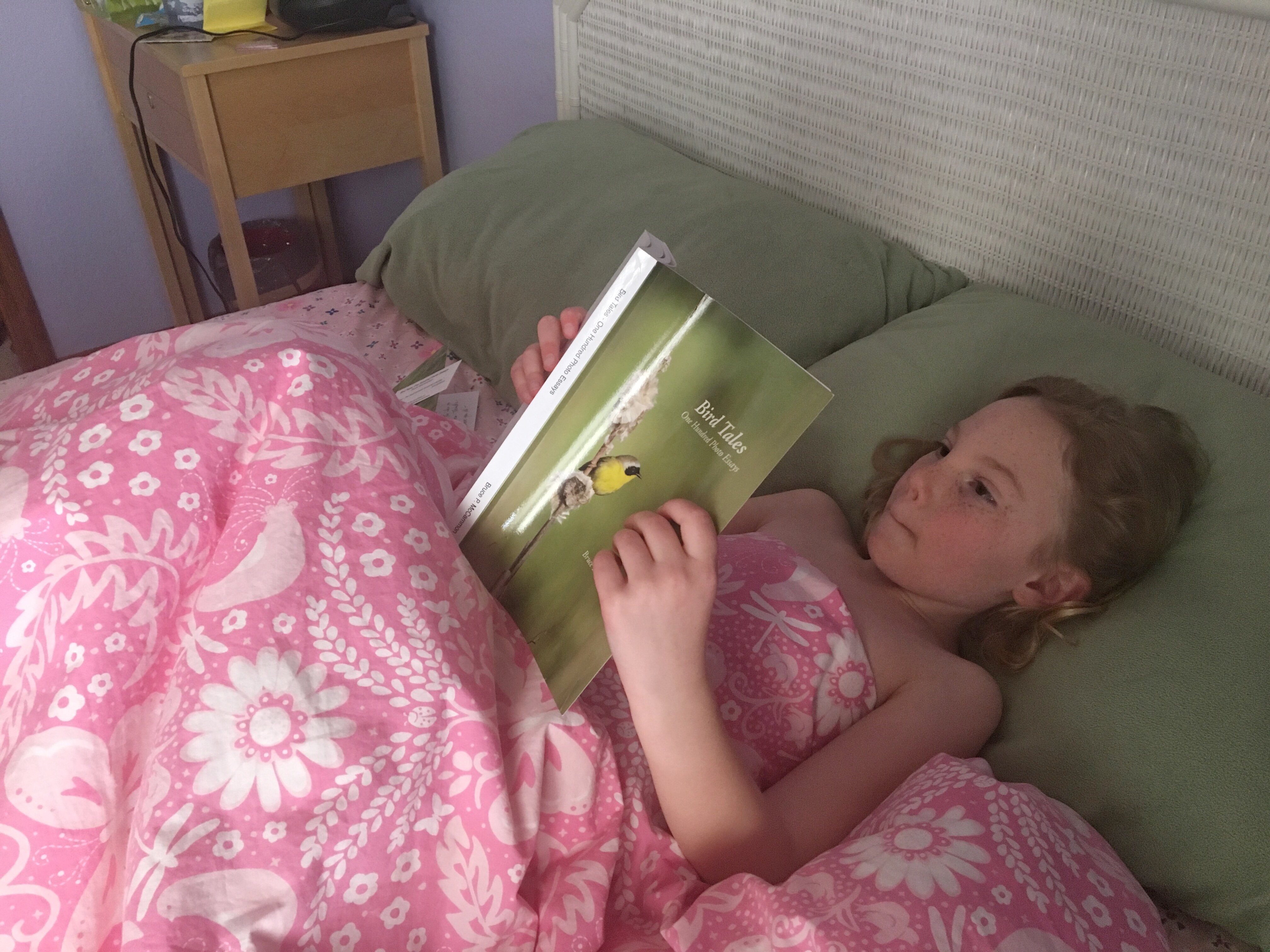

I spent much of today engaged with the small Anna’s Hummingbird. 30 minutes before sunrise I was positioned to watch a heated feeder on our patio. Center stage for the North Central Washington Audubon Society hummingbird project. I had my tally sheet, binoculars, and coffee. The camera was poised to look through the glass to the feeder. Focus and exposure were set.

The observation period for the NCWAHummerproject began at 07:16. The first hummer flew to the feeder at 07:10. Six minutes early. Guess it didn’t get the memo, It stayed there for 38 minutes. Drinking every 3-5 minutes, it was alert but very calm. For the next hour it sat at the feeder, jousted with an interloper, and visited 3 perches.

I had time to think about these small birds. Existing during a time of climate change, increased planting of nectar sources in back yards, and increased use of feeders, the Anna’s is expanding its range to the north and east. Prior to this survey day I entered a conversation with a lady in Colville, WA – hours to my north and east. She was photographing her first Anna’s – in the snow – at 10 degrees F. Amazing.

So, with thoughts about issues directed at this species, I decide to launch my thoughts about a myth, range expansion, and nomenclature on Facebook. The post I made is below. I welcome your thoughts.

An age-old question ponders the wisdom of feeding Anna’s Hummingbirds in winter. North Central North Central Washington Audubon Society recently created a Hummingbird page on their website (https://ncwaudubon.org/hummingbirds/).

Here you will find published, peer-reviews article that provide an answer. Take a look.

Another new thought about Anna’s Hummingbirds is how to refer to them as they expand their range. We now have over-wintering Anna’s in Colville and Kettle Falls, Washington. First time birds. Take a look at the beautiful images provided on Facebook by Joanie Christian. Anna’s are native to the continent but new to the far eastern parts of Washington. Can they be called “indigenous” in the new area? I think it might be that they are “native, newly-arrived”. Your thoughts?

The photo below was taken today in Wenatchee, WA. The bird sat on the heated feeder for 38 minutes, taking nectar about every 3-5 minutes. It still ran off another hummer that made advances in the feeder. The bird was alert and active at 23 degrees. I watched it on several perches and at the feeder for an hour. Yes, they are here in winter. To top that, we also know after monitoring 5 nests last summer, again – in Wenatchee, WA. that they are successfully breeding and raising young

Celebrate the Anna’s!!!

Happy Holidays.